We are ending another great year of selections for our Record of the Month Club with a record proper for introspection, blissful listening, resting, and palette cleansing. This last record of the year could also be heard as a beginning to 2024–a nice, calm, reflective ending merging with a beginning.

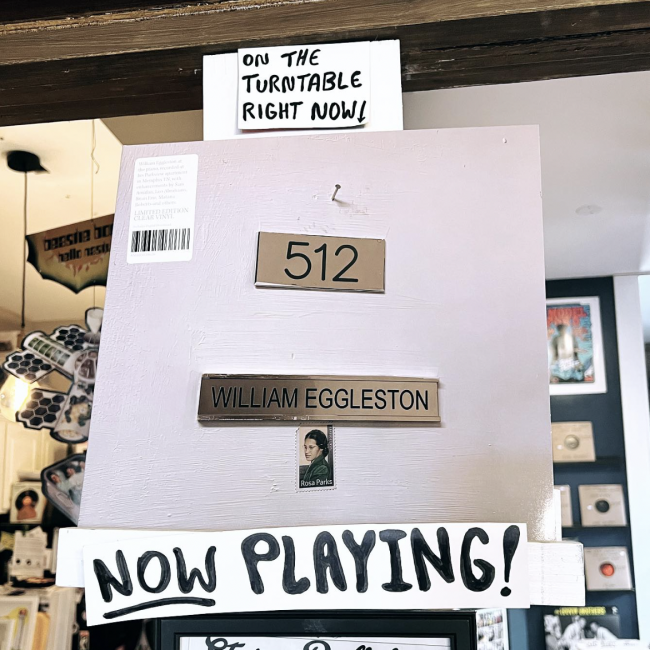

William Eggleston, most notable for his photography, is also a talented pianist. His second album on the Secretly Canadian record label is a beautiful glimpse of improvisation and standard songbook playing in the form of a semi-live, field recording-type effort. Recorded at Eggleston’s apartment in Memphis in 2018, 512 is a beautiful slice of music from an artist aging gracefully with his grand piano always waiting.

We first heard this record upon its release back in early November, not thinking it would be part of the Record of the Month Club at first, until the record kept finding its way onto the shop turntable. We kept spinning it! Then it was obvious, we should make this the final selection of 2023.

Club Members will be getting a copy of the limited, clear vinyl pressing of the album. We’re gonna start shipping them out asap!

More about the album:

It also happens to be true.

Back when Eggleston released “Musik,” he was recognized already as one of the most original and significant visual artists of the 20th Century. It’s not a stretch to claim he legitimized the use of color photography in pursuit of fine art.

“Musik” announced the arrival of Eggleston the musician: a spontaneous creator who synthesized – quite literally, with his Korg O1/W FD digital keyboard – a deeply personal and profoundly powerful body of work. His solo fantasias reflected influences absorbed from a lifetime’s exposure to the compositions of classical-music masters like Bach and Handel, folk and country staples, the Great American Songbook, gospel, and more, all processed through the filters of a doggedly idiosyncratic artist’s sensibilities.

“Surprising as “Musik” unquestionably was, its successor, “512” – named for the number on Eggleston’s front door – is no mere sequel.” Working again at his apartment in Memphis with producer Tom Lunt, Eggleston embraced traditional pop, folk, and gospel styles more directly in a collection of four standard tunes, along with “Improvisation” and “That’s Some Robert Burns.” In place of the mercurial digital keyboard he previously used, Eggleston plays a magnificent Bösendorfer grand piano, rich with sonic overtones and historical allusions.

In a more dramatic departure from the freewheeling soliloquies of “Musik,” Eggleston is heard in the company of other musicians on “512” – though none of them ever actually shared space with the artist. True, distanced recordings and virtual ensembles have become familiar especially in the years since pandemic isolation was imposed in 2020. But Lunt had something different in mind.

“I was thinking about the home recordings of Charles Ives,” the producer said, referring to the rough-hewn but magical songs the great American composer recorded between 1933 and 1943.

“They were so completely genuine,” Lunt explained. “If he made a mistake, the mistake stayed in, and he responded to it. He would make everything right at that moment.”

Proceeding from that inspirational starting point, Lunt spent a few days in Memphis recording Eggleston alone at the piano in his room. Then he imagined how to invite other musicians into Eggleston’s space, virtually—and which artists might be suited best to such a special invitation. “I wanted the other musicians to emerge as spirits passing through, inspired to join William,” he said. “So many wonderful artists have visited 512.”

On careful consideration, Lunt selected Sam Amidon, who he’d met years earlier while working on a Liam Hayes album. A vocalist and multi-instrumentalist from Vermont, Amidon is celebrated both as a solo artist and as a participant in projects led by Bill Frisell, Jason Moran, and Nico Muhly, among others. Amidon, working in England at the time, in turn enlisted another distinguished solo artist and arranger: Leo Abraham, whose collaborative credits include Brian Eno, Jarvis Cocker, and Imogen Heap.

The two had worked together previously on Amidon’s 2017 Nonesuch release, “The Following Mountain,” which vividly demonstrated their shared knack for making folkloric sources sound fresh and wild—an affinity that would serve them well in fashioning new contexts for Eggleston’s thoughtful and assertive piano recordings.

What’s more, working at a physical distance felt oddly appropriate, Amidon notes, since Eggleston did all of his talking and thinking at the piano keyboard. “He leaves that space in the playing, where you can kind of hear him thinking about where to go next,” Amidon said. “And even though the music is very beautiful and very consonant, it has this ‘happening’ kind of quality: we’re in the space not only while he’s playing, but while he’s remembering all these melodies from his youth.”

In addition to Abraham’s subtle synthesizer and electric guitar and Amidon’s folksy banjo and fiddle, the two collaborators enlisted other musicians to share Eggleston’s dreamlike space. The first sound on “512,” Eggleston’s voice aside, is bell tones generated by ambient-music legend Brian Eno, shimmering around the ruminative piano on “Improvisation.”

Other collaborators seem to materialize at a distance; on “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” it’s almost as if Matana Roberts happened to be wandering by on the sidewalk outside, saxophone in hand, and felt gripped to partner with Eggleston’s reverie. Amidon’s gentle contributions enhance “Ol’ Man River,” “Over the Rainbow,” and “That’s some Robert Burns”—the last a meditative reflection inspired by the Scottish poet and songwriter of the title.

For the epic rendition of “Onward Christian Soldiers” that closes the album, bassist Mikele Montolli and drummer Seb Rochford seem to form an almost impossibly empathetic trio with Eggleston. What Abraham hoped to conjure, he says, is the impression that the music was all coming into being at the same time.

“That approach was partly influenced by Frank Zappa’s arrangements of improvisations, where he’d arrange his guitar solos for big band,” Abraham explained. “It’s kind of an amazing thing: a way of framing a chance event as if it were planned.”

You could say that what resulted, here and throughout “512,” is art very much akin to Eggleston’s world-changing photography: something that feels instantly familiar at first brush, yet over time and with closer examination reveals hidden depths. It’s an artistry hidden in plain sight, a subtle magic that demands contemplation.

What’s more, the approach taken by Lunt, Amidon, and Abraham on “512” provided an opportunity for Eggleston himself to experience the surprise and delight his art has provided for countless others.

“I’ve never heard anything like it,” Eggleston said, grinning. “It’s very modern.”